Left Turns and Hanging Things on the Wall: Interview with Philosophy Professor and Morningsiders Lead Singer, Magnus Ferguson

This week’s interview is with Magnus Ferguson, a Collegiate Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Chicago and lead singer of the folk-pop band, Morningsiders, known for songs such as “Empress,” “Honey Hold Me,” and “Don’t Let Me.”

Magnus met fellow bandmates, Reid Jenkins and Robert Frech, while they were all students at Columbia University. Upon graduation, the three decided to pursue the band full-time and spent the next three years touring the country. Their music attracted notice. Notably, “Empress” was featured in a Starbucks commercial featuring Oprah Winfrey, and the band was featured in Taylor Swift’s public playlist, “Songs Taylor Loves.”

Still, life touring was starting to wear on Magnus. He began spending his free time emailing old professors and digging into their reading recommendations from the road. Eventually, he confronted the question: Maybe philosophical texts weren’t meant to be read from the tour van? Maybe there was something appealing about grad school? He applied and was accepted into a PhD program, and the band decided to strip the project down to its bare bones. Together they asked the question: What if they stopped touring and got back to what they really loved doing - making music together?

The plan worked. Today, Magnus is a full-time professor and Morningsiders is still making music (the band was most recently in the studio a week before Magnus and I chatted). Fans of the music haven’t gone anywhere either - the band has 761,000 monthly listeners on Spotify.

It’s not every day you meet a philosophy professor who is also the lead singer in a popular band. There was a lot I wanted to know. What was it like to pursue the dream of making music after college? Did he feel scared when he decided to go back to graduate school? What ultimately helped him tune into the path that was right for him? What’s he learned about creativity at this point in the journey?

We talked about all of that, as well as:

The romance and discomfort of touring

Getting inspiration back after the band demonetized the music

Learning to set down false stories

Becoming more than what you do

Taking comfort in creating a body of work

Note: The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length. While every effort has been made to preserve the integrity of the conversation, please be aware that the quotes may not be verbatim but reflect the essence of the dialogue.

Let’s set the scene. How would you describe your occupation?

It depends on the room I'm in or who I'm speaking to, but I think the answer is that I am an assistant professor at the University of Chicago. I think of myself as being an academic which involves equal parts teaching, researching, and writing.

I don't often lead with ‘musician,’ but I do put lots of effort and energy toward Morningsiders, which is the band Reid, Rob, and I started while in college at Columbia.

I want to dive into your story. You started the band in college, pursued it full-time and toured the country after graduation, and eventually went back to school to get your PhD. What’s the story that got you to where you are today?

I met Reid, who plays violin in the group, at a New York meetup before orientation. There was a blizzard that neither of us knew about so we were the only two people to turn up. We had coffee and realized that there were all these connections we didn't know about. For example, Reid lived on the same street as my high school. So we connected freshman year and he told me he was looking for a songwriter to make music with. We then connected with Rob, who plays piano, through mutual friends, and things clicked right away. There wasn't a lot of thought put in. We just met up. We played a Mardi Gras party. We played at open mics. It was really nice to have this miniature club that grew and shrank over the years to move through the chaos of undergrad. It was nice to collaborate with musicians who I was in awe of, and who were technically and academically years ahead of me in terms of their musical knowledge, but who were game to play my songs. We grew very close, and the band served as a very balancing piece of my college experience.

I didn't have the easiest time in undergrad and that was partly of my own doing. I wasn’t very organized or mentally healthy in a lot of ways. I always limped through the end of finals. I made a lot of retreat moves throughout undergrad, one of which was to become a Religion major. Honestly, my rationale was just that the class sizes were about 6 to 8 people, half of whom were graduate students, and it was in a very non-competitive corner of the university where I could really get to know professors in seminars. That was another very balancing thing and ultimately how I was exposed to a lot of the texts that I spend time with now.

At the end of undergrad, the thing that had the most momentum, brought me the most fulfillment, and seemed crazy not to pursue, was the band. We coalesced around that, and for the next three years following graduation, we were touring, recording, and playing festivals.

Let’s talk about that moment at the end of undergrad. There’s a ton of peer pressure to go down the well-trodden paths of finance and consulting or go get another steady, corporate job of some kind. Yet you recognized that there was this other area you were really passionate about and decided to pursue it. What gave you the conviction to do something that other people might not understand and that was a big departure from what a lot of your peers were doing?

I did feel that it was a different thing. I have this memory of coming across a job fair at school and seeing my fellow students in lines with their suits and ties and dress blazers, carrying around folders with their resumes. I thought, “I can't pull myself together for that. I'm not even in a place to try and elbow my way into those conversations.” Maybe that self-doubt helped me seize onto the band.

But really it was friends who got excited about the music. They’d turn up at shows without me even telling them, bring their friends, and share the songs. The idea that affirmation was happening outside of my view was so exciting to me. That motivated me even though I didn’t have a “clean, stick the landing” job into a position that followed an internship. The band made me feel like I was working towards something, even if it wasn't the same thing as the people around me.

What were those three years of touring and that period of life like for you?

It's weird to look back on them because it was simultaneously very romantic and very uncomfortable. It was really intense and very confusing to all of a sudden have the full day open for writing and rehearsing. Early on, I struggled a lot with getting inspired. I would get confused about whether I was just regurgitating the stuff I was listening to or creating something from my own voice and perspective.

Touring was a blast, though. I got to see huge swaths of the country I would never have seen. I met a lot of people and connected with many acquaintances and friends of friends. But it was mostly car rides and seat belts and crashing at friends’ parents’ places, which is a strange feeling. You’re not eating super healthy and having too many beers after the show. I never fell into a rhythm where it felt sustainable. I have a lot of respect for people who build a career in music in that way.

Even just a year or two in, I was already sending former professors emails asking them what I should be reading. I’d ask if I could informally audit a class while I was in New York. I’d be sitting in the van reading some dense text that I was struggling to find a way into, and it dawned on me at a certain point: If I'm spending all this time on my own trying to read Kant, shouldn't I just go read Kant somewhere where people could show me what’s going on? I was also in a relationship with someone I met at Columbia, who I’m now married to, and we were figuring out how it was going to work. Conversations like: How is this going to work if I’m out of town three out of four weeks, taking odd jobs, and playing jazz cocktail parties trying to make rent? The idea of graduate school, where they pay you a pretty modest but consistent stipend every month, and you have things like healthcare, and you know where you're supposed to be for a number of years, was appealing. The stability and focus was incredibly exciting to me.

It sounds like the decision to go back to graduate school happened somewhat organically. At the same time, Morningsiders was having a lot of success. You were getting noticed and had songs that were widely recognized. Was it hard to walk away from that path?

It was hard to not feel like I was betraying the group, but I think that’s kind of a false story. Part of it was that our pianist, Rob, who works in the music industry and has incredible intuitions about music as a business, really opened my eyes to what streaming could do. He said, “Our streaming is growing independently of how many gigs we’ve played.” After I got my acceptance to grad school, we hatched this plan based on asking: What if we just stripped the music down to a skeleton crew? You lose a ton of money touring - you have to rent a van, occasionally splurge on hotels, pay for gas, all this stuff. When you're opening, you're getting paid a couple hundred bucks a show, so it makes no financial sense. By deciding to stop touring, we stopped hemorrhaging money and basically turned Morningsiders into a digital media startup of sorts. The idea was that we would make songs, put them up on Spotify, and that was kind of it. We weren't fronting the cost to sell T-shirts. We weren't selling tickets. We weren't making music videos. We were just meeting up when we could and recording music. It felt weird to strip it down like that, but I think the idea all along was to refocus on the thing that we were actually good at and prepared to do, which was making music together.

You’re still making music together and were just in the studio last week. What I love about your story is that you found a way to keep making music in a way that worked for you and the band. You are a professor and a musician. What do you think gave you the courage to find a path within music that worked for you?

I've never thought about it in terms of courage. One thing that helped is that I got a ton of inspiration back once we stopped touring when I wasn’t trying to have the music be the way I defined myself. It wasn’t even a side hustle at that point. We decided we weren’t going to rely on royalties or anything like that for our incomes. We were all doing our own things. Reid is a musician in New York working on his own projects, as well as other people’s. Rob has a job in the music industry. It helped that none of us were desperate to sign a deal or headline a festival. We could take months, sometimes many months off, where none of us would do a thing, and then the songs would appear slowly, and we would start sending them to each other. I think demonetizing it kept it alive and kept it interesting.

It also sounds like taking away any expectation of what it had to be was its own kind of unlock.

I think that's totally right. I was really in my head for a while. Was I writing stuff given what I knew about which songs were doing well and which songs weren't? Or was there something of my own voice in there? Untethering myself from expectations allowed a lot of the personality that makes our music distinctive to come back.

At this point in your life, what have you learned about creativity and what keeps you inspired?

I don't feel very in control of it. I often get a lot of ideas when I'm very busy with something else, usually at the end of the academic quarter when I am supposed to be grading or pushing out my own research. I hear about people who set aside a multi-week block and curate a space for creativity. I’ve never been able to do that.

For me, it was more about building a lifestyle where, when inspiration struck, whenever it was, however inconvenient, I could find a way to funnel some energy towards it, and when it went away I could turn to other parts of my brain and not just wait around for it to come back. I feel the same way about research and teaching. I tend to be a much better writer when I'm teaching because a whole chunk of my day is already accounted for. I know where I'm supposed to be. I'm interacting with people. I'm getting excited. I'm getting a lot of energy from students. I can then redirect some of that energy towards writing.

Days like today, where I wake up, and I'm just supposed to work on these long-term projects, tend to be harder for me. I'm most creative when I'm busy with other things. I can’t really approach it head-on.

I work with clients who are often in the process of building something or sharing work publicly for the first time. You’ve done that a lot yourself. What advice do you have for people who are on the precipice of sharing something but feeling afraid?

I came across this Ira Glass essay really early on in college called “The Gap.” He says something to the effect of: the reason that you are pursuing creative work and putting it out in front of people is because you have really good taste. You know what you like. You know when things have this extra sparkle to them. Because your taste is good, you can tell that what you make is pretty mediocre. You can see that you're not as good as your taste is at making the thing, and you can instantly spot where it falls short. That’s why he thinks a lot of people with good taste and creative ideas don’t actually pursue the ‘making’ part of creative work. They just think they are good consumers of art or meant to be critics or something.

His solution is to understand that every time you make something, the gap closes a bit and your output will start conforming more to your taste. You just have to go through hundreds of repetitions. There are all these myths with creative work. We think that the first Strokes album was perfect, and they just came out of the womb already cool and smoking cigarettes ready to ride all the way to the top. I don’t think that often happens. At least for me, what happens more often is that you're just slowly hanging stuff on a wall. Eventually, the wall starts to look complicated and distinctively like you because it's averaging together.

The first step is tough because it’s the only thing on the wall. It got easier for me once we had more music out because it meant that I could take more risks and those risks weren’t going to pull the band into a different genre or something. They just added some color to the wall. Focusing on a body of work instead of a viral single relaxes me about putting my work in front of other people because it reminds me that what I want is for them to discover the catalog. I imagine it's sort of like building out this blog. If you were to post an interview and it doesn’t make the rounds, you might think you’re not a very good blogger and shut it down. Whereas there’s something amazing about being a little late to the game and discovering a whole backlog of interviews and insights, and then wondering what comes next. I love it when I stumble across artists who have an enormous volume of work and have been keeping their heads down and just making stuff because I get to track the story and dive deep into it. The musicians I’m most in awe of are the ones who just compulsively make things. They leave it to you to deal with how to put it all together.

That is going to stick with me for a long time. It also makes me curious to ask you about music. I imagine it might have been tempting or even easy as you were applying to graduate school to say, “Should I just give up music altogether?” But you didn’t. Why has it been important for you to continue making music? What do you think you’d be missing if you’d given up music altogether?

It was confusing at first. I was worried people would take me less seriously as a teacher or scholar if they found out I was a pop-oriented musician. I sometimes joke that there’s this graph. On one axis is ‘age’ and the other axis is ‘how cool it is to be in a band.’ There are for sure some dips as you get older, and it’s sometimes a tough pitch to say, “My thirty-something-year-old friend is in a band. Do you want to go watch their show?” I was really self-conscious about it, but it probably made things more weird to try and hide it.

I think it was a symptom of buying into another myth of what an academic looks like and needs to be. As the years have gone by, I think I’m relaxing my hold on that story. It's not that sometimes I wake up and I put on my academic clothes, and I have scholarly expressions on my face, and then sometimes I put on a ball cap and looser clothes and go to Greenpoint or something. I mean, that does happen. I probably am different in those spaces. But I think what music saved me from was making the same mistake in grad school that I had in pursuing music as a career, which would be to say, “I’m in grad school and that’s all you need to know about me.”

When I look at a lot of my friends who are musicians now, I can see that they are more than one thing. They show apartments to make money, fix up buildings, teach, and make other kinds of art. They have complicated, mature layers of themselves beyond music. I think that’s saved me from censoring myself in the name of a made-up template.

You’ve mentioned the idea of the false story a few times – the ideas we have about how we should look or behave. It seems like you’ve gathered a lot of wisdom over the years about how to set those stories down and embrace being multifaceted. What helps you embrace different parts of your identity?

There’s an idea in songwriting that Reid often reminds me of, which is “show and don’t tell.” A better lyric than “I'm so depressed and sad right now” is something about how you notice your hands are shaking as you drink a glass of water. It started feeling really good to not have to say, “I want to be this” or “I want to do this” like we did in college. I love when I meet someone and it’s clear they’ve been themselves for years, and there is no short version of the story of who they are.

In the end, the stories I heard about what success looks like or what being an academic looks like were so wrong, or at least wrong for me, even if those stories were a big part of my initial interest. If I had clung to that original, totally uninformed picture, I wouldn't be very happy when things turned out differently. I think it’s more interesting to focus on the output than the job description.

Many people I interview for the No Directions blog have created lives that are uniquely theirs in terms of how they live, work, and build their lives. What does the life that is uniquely yours look like today? What are you building towards?

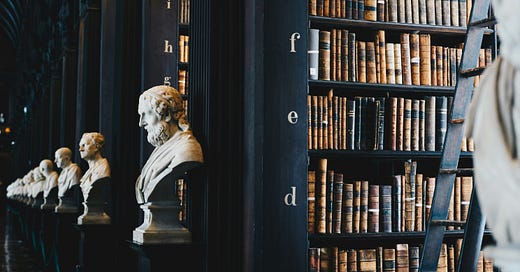

I’m very happy right now. I teach the history of philosophy to young people, some really remarkable 19-and 20-year-olds, who are just striking out on their own. It’s a privilege to be able to think with them and to share questions and texts with them that I think are deeply moving and worth spending time on. The best part of my academic job is that I have to learn constantly. Teaching is really just an excuse, for me, to allow yourself to be curious and to share your curiosity with others. I get to talk about the things I’m most interested in with brilliant young people who share those interests.

Still, I'm not locked into a permanent tunnel to retirement and sometimes that’s unnerving, but maybe it’s also a good thing. We’re making really fun music as Morningsiders. We recorded last week, and we're working together better than we ever have before. I want to keep watering these two plants as long as I'm still feeling inspired, and I can keep learning and changing. Going to graduate school was a huge left turn, and it ended up being the best possible thing for me. So, I'm open to the idea that there are a few more left turns ahead of me.